Language is an important part of our human heritage. It is the vehicle through which we communicate our innermost thoughts and feelings, as well as transmit culture, identity, ideologies, and values from one generation to another. This means that the language of a people essentially represents their unique existence.

However, as shown by recent research, humanity is losing its languages (and, consequently, diversity) at an alarming rate. According to the 2016 edition of the UNESCO Atlas of Languages in Danger, a whopping 40% of the world’s known languages are in danger of disappearing.

“When you study the history of the development of the French language or any other language for that matter, you would discover strong cultural or historical links, and if you let any word of it die, you would have lost a part of your history or culture as a people. For me, a language is like a memory card with encoded messages that you pass from generation to generation. And without your culture and history, what is your identity?” – Abdoulaye Barry.

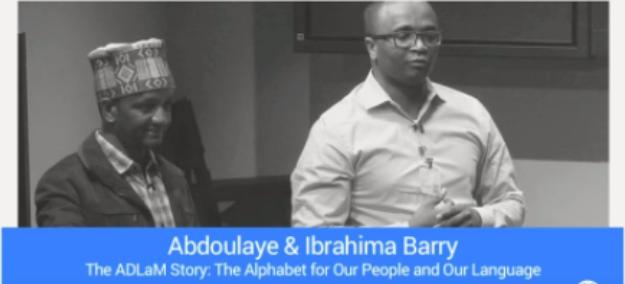

In the first part of this series, we recount the inspiring story of two brothers who took the initiative – at ages 10 and 14, respectively – to create an alphabet for their native language.

The two US-based brothers, Abdoulaye and Ibrahima Barry, were born and raised in the Republic of Guinea. At the time, letter writing was a crucial part of communication, since there were no telephones available. To write the letters in their language, Fulani (also known as Pular or Fulfulde), the natives had to use the Arabic alphabet. This posed a lot of challenges, as several Fulani sounds were missing from the Arabic alphabet, and there was no standard way of using Arabic letters to represent them. This created a lot of ambiguity on the side of both the sender and the recipient.

Driven by a strong desire to facilitate written communication in the Fulani language, Abdoulaye and Ibrahima set about the task of creating an alphabet in which the Fulani language could accurately and effortlessly be written. At the time, they did not know the amount of effort required to accomplish their goal; they did not anticipate the obstacles they would later encounter. They obviously knew nothing about the concept of endangered languages either. All they knew was that they were going to make this happen.

It is now 2020 – over 30 years since the brothers first embarked on this journey. Books have been written and published using the script they created, known as ADLaM, an acronym for the Fulfulde expression meaning “the alphabet that will prevent a people from disappearing”.

ADLaM is now encoded in Unicode – thanks to the resilience of the brothers, as well as the Script Encoding Initiative managed by Deborah Anderson at the University of California. Additionally, it is currently supported by major digital platforms such as Google and Microsoft. The brothers also say that the ADLaM script is not limited to the Fulani language (which has over 40 million speakers worldwide), but is also suitable for writing several other African languages.

Nevertheless, it is not yet the end of the road for Abdoulaye and Ibrahima. Their goal is to see ADLaM fully supported by most – if not all – digital platforms. In their own words, the survival of any language today depends largely on its presence and use in the digital space. It is for this reason that Translation Commons works tirelessly in collaboration with individuals, UNESCO, and other organizations to ensure that “no language is left behind”.

Click here for more information on the Language Digitization Initiative run by Translation Commons.

Stay tuned for the second part of this series!